PROTECT YOUR DNA WITH QUANTUM TECHNOLOGY

Orgo-Life the new way to the future Advertising by AdpathwayWe’ve all heard warnings about how we treat each other online. Don’t read the comments sections of your blog posts, the people there are assholes! Interview for that job in person, if you can, they’ll like you better than if you were just on a screen. Let’s meet face-to-face to have the talk, etc.

It’s clear that there are a lot of advantages to online communication. Privacy, control, connecting people who wouldn’t otherwise be connected, to name just a few. Technology in general can allow us to overcome barriers, and technology-enhanced communication is no exception.

But none of these advantages undo the fact that interacting with each other online can be more difficult. Even if we’re trying to empathize and understand each other, the Internet is not always the most fruitful ground to do so.

One important diagnosis here is about the amount of information that tends to come across in online interactions. Think about if you’re having a discussion with a mutual friend on a Facebook post instead of at a gathering in someone’s house, if you’re venting to another friend over text instead of in the pub, or if you’re interviewing for a job on a video call instead of in real life. The words you use might all be the same, but there’s less to go on overall.

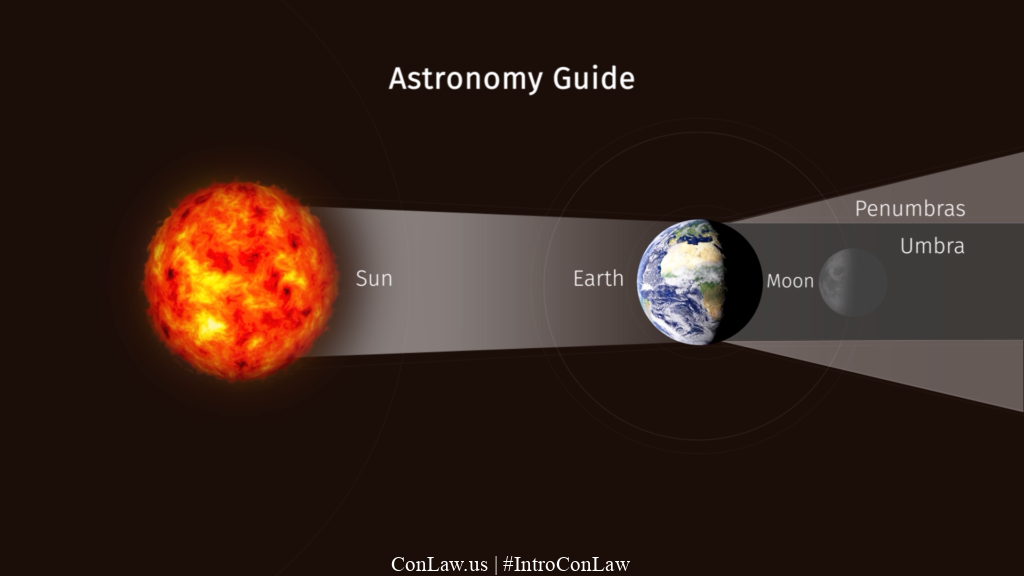

“Information,” here, should be taken very broadly. Not just a fact about what someone has said, but the emphasis in their voice, their body language, the way they’ve said it, the overall environment beyond the video screen, etc. Think about the difference between seeing two breakfast menus with pictures of food: one in color, another in black-and-white. Even if you can still see the same items (the hash browns, the beans, the toast, the avocado…), the former picture is more likely to give you a better impression of how delicious it would be. The breakfast would be more vivid in your mind—perhaps you can almost taste it.

On average, we simply don’t share as much information in online spaces as we do in the physical world. And this might be a reason why online communications can be more difficult. Just like a more colorful picture might make you hungrier for breakfast, a more vivid idea of who you’re speaking to might help you to imagine their perspective. To see them as a real person, as a fellow human being, rather than a simple avatar or a name.

This problem isn’t a fatal blow for the potential of online communications. There’s nothing inherent about the ways we communicate in online spaces that means less information will always come across, it’s more of a contingent generalization about the online tools we tend to use a lot of at the moment.

Indeed, this even seems to be a problem that’s been steadily getting better. Think not just about the ways in which online communications are increasingly better at mimicking physical ones (more use of voice messages, video calling, etc), but the ways in which online settings allow us to communicate differently, and to get different things across. Perhaps a colon and a bracket were originally just meant to convey a similar sense of tone to a physical smile or a frown, but the range of emojis we have now go far beyond what a face can easily express. We have this whole new shared language with its own developing history, of small pictures used sometimes ironically, sincerely, provocatively, or suggestively. In a lot of online communications, we can also use punctuation and short-hand creatively (imagine responding to a long message with just an ellipsis), we can add reactions directly to other messages, send links to images or further resources, use memes.

Remember that information isn’t simply a numbers game, where the more words there are, the more information there is. Sometimes a small image, used well, can deliver a lot. Even a short story can sometimes capture you more than a longer one. Quick memes can reference shared histories, political values, and cultural moments.

So far, I’ve only mentioned a simple account of a general difference between online and physical communication: the information that comes across. But this diagnosis can be refined.

The ease with which we treat each other well isn’t just about how much information comes across, however broadly that’s construed. Also relevant is what kind of information comes across. And there’s a sub-category of information that can be particularly difficult to get across in online contexts. To see that, let’s think about the additional control that we tend to have online.

As I mentioned above, there are many ways in which increased control over our information is a good thing. It’s good for privacy, for safety, for freedom, for our self-determination and self-presentation. But there’s at least one way in which it might be bad for how we treat each other. Because of that increased control, there’s so much information that we don’t share, even when we’re given a wider choice of formats to communicate with. Sometimes because of the social norms in question (it makes sense to introduce yourself at a party, but not necessarily on a mutual friend’s Facebook post). Sometimes because we don’t even know what information might be important to communicate (our posture or expression might tell someone a lot about how we’re feeling without us even being aware of it). And sometimes just because we don’t want to share the information—such as if it’s about our vulnerabilities, like our nerves or hesitance. We curate how we come across much more online, whether it’s out of explicit choice, social norms, or not knowing to do any better. Even on a video call, we’re said to spend more time looking at our own screens to check how we look, rather than at the people we’re talking to.

It seems likely that a lot of this kind of information is exactly the right kind to enable us to better understand, empathize, and care for each other. We might find it easier to see each other as humans when we get not just a bigger picture but a more rounded picture: one with all the idiosyncrasies, mistakes, and vulnerabilities included. Perhaps when you can see my nervous stance and hear my strange laugh, my personhood might seem more vivid—like a colorful breakfast.

This more specific diagnosis isn’t supposed to be a complete account of why online spaces are sometimes less fruitful grounds for care and compassionate communication. But it does seem to be one aspect that can make a difference, and one worth doing more theorizing about.

Even if it is true that this kind of information is much harder to get across in online communications, we shouldn’t be entirely pessimistic. Control, when we do have it, still comes with a number of advantages. And it’s also likely to be another way in which we continuously improve, the more we speak to each other online. Just like we’ll keep getting better at what we do explicitly communicate, so too will we get better at reading the implicit information—the doubts, hesitations, vulnerabilities, etc.—between the lines.

Lizzy Ventham

Lizzy Ventham is a postdoc on a privacy project at The University of Salzburg. Her research interests include practical reasoning, non-moral normativity, empathy, and the philosophy of technology.

.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·