PROTECT YOUR DNA WITH QUANTUM TECHNOLOGY

Orgo-Life the new way to the future Advertising by AdpathwayDemocracy has been on the defensive for the last decade and more. Right-wing populist and authoritarian leaders dismantle democratic checks on state power, repress opponents, and try to control once-autonomous institutions such as the media, corporations, and universities. Citizens lose trust in their democracy. Elites and the public alike—intent on defeating the other side—seem happy to abandon democratic principles. Rising inequality means that more than ever, plutocrats can translate their wealth into political power. Unscrupulous elites prosper, be they authoritarian populist politicians such as Donald Trump, media moguls prepared to sacrifice democracy for profit such as Rupert Murdoch, or billionaire social media owners such as Elon Musk, who are happy for their platforms to disseminate extremism.

Democratic backsliding and autocratization have coincided with the rise of deliberative democracy as the most popular approach to democratic theory—also now involving a host of practitioners seeking to apply some of its ideas. Deliberation can be defined minimally as “mutual communication that involves weighing and reflecting on preferences, values, and interests regarding matters of common concern,” though particular theorists elaborate beyond that minimum in different ways.

Deliberative democracy is most readily conceived as a deepening project, one that is attuned to the deficiencies of existing democracies—notably (though not exclusively), of the sort found in liberal democratic states. In this light, democratization can be interpreted as the building of deliberative capacity of a system—not just or even primarily in the establishment and consolidation of the familiar institutions of electoral democracy. This capacity can be understood as the degree to which a political system has structures to host deliberation that is authentic, inclusive, and consequential. The search is then on for practical ways to enhance deliberative capacity, be it by making parliaments and constitutional courts more deliberative in their workings, adding explicitly deliberative forums (such as citizens’ assemblies) to the institutional mix, or seeking better deliberative conditions in the broader public sphere.

But does this emphasis on deepening mean that deliberative democracy is ill-equipped to help defend democracy against backsliding and autocratization? Not necessarily. For deliberation places meaningful communication at the heart of democracy. And the contemporary crisis of democracy is in large measure a crisis of communication. The changing media landscape means that it has never been easier for political actors and citizens to give voice, but the resulting expressive overload means that reflective spaces and capacities can be in short supply, such that instant responses to signals crowd out more thoughtful ones. Simplistic slogans, misinformation, lies, disregard for truth and logic, polarization, and incivility flourish in an increasingly “diabolical soundscape,” and bad actors like Trump, Murdoch, and Musk exploit opportunities for the sake of political and financial advantage.

Deliberative democrats can stress in response the need to strengthen and deploy deliberative capacity. What might they contribute here?

We might start with democratic innovations, defined by Mark Warren in his 2024 presidential address to the American Political Science Association as “practices and institutions a.) that function to deepen or widen democracy; b.) that fall outside of the older, legacy institutions of representative democracy; and c.) that supplement rather than replace these institutions.” These innovations are generally deliberative in principle, recruit lay citizens to processes such as citizens’ assemblies, citizens’ juries, citizens’ panels, consensus conferences, deliberative polls, deliberative town halls, and participatory budgeting. They have exploded in popularity in the last decade and more—ironically, at the same time state-associated democracy has retreated. This alone suggests that such innovations are insufficient as the deliberative response to contemporary state democratic backsliding. Rather than merely supplementing legacy institutions (as Warren suggests) they can be interpreted as moments in the life and possible strengthening of deliberative capacity not completely tied to the faltering institutions of the liberal democratic state.

Transnational democratic innovations are beginning to appear, in the form of a Global Assembly on the Climate conducted in 2021, and several Europe-wide ones on a variety of issues. More significant are the well-known activities of global civil society. While its representational deficiencies are also well known (such as a preponderance of organizations based and financed in the Global North), its organizations and activists help render global governance more inclusive, responsive to a wider range of concerns, and deliberative. Global civil society has contributed to the emergence of inclusive and consultative norms, reflected for example in the process that yielded the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015 (however imperfectly these norms were realized in practice). Such norms (and others involving human rights) can diffuse internationally and carry over into domestic politics, while activists can learn from and be supported by their counterparts in other states.

Social movements can be key features of the public sphere with critical and sometimes confrontational distance from the state. Social movements (such as Occupy and Extinction Rebellion, citizen movements for constitutional change in Chile and Iceland, Fridays for the Future concerned with climate change) can themselves be important locations for democracy in their deliberative and inclusive internal practices. The stakes are much higher in countries such as Myanmar, where civil resistance confronts violent military dictatorship.

In social networks both online and offline can sometimes be found sites where citizens can engage with different others and perhaps reflect on their own opinions and interests, as well as those of others. There is a big difference between the kinds of communities that can organize themselves to good (democratic) effect on Reddit, and the individualization and extraction for profit that Facebook promotes.

Some movements disillusioned with working through dominant legacy institutions seek instead to change everyday life. For example, “sustainable materialism” attends to how food, energy, and clothing get produced and consumed, while also developing a democratic “prefigurative politics.”

We can ask how the various sites and practices I have described can collectively contribute to the resilience of democracy in the face of threats and challenges. Different sites and practices can vary in the extent of their contribution in different polities, and it is important to stress the capacity of the deliberative system as a whole—not just its component parts, be they in civil society, social movements, social networks, democratic innovations, parliaments, or the media. Deliberative capacity can also extend to citizens who might be attracted by populism and authoritarianism. Here it is a matter of constructing discursive bridges (the opposite of dismissing people as “deplorables,” as Hillary Clinton famously did). Discursive bridging begins with identifying the discourses that such citizens might be attracted to—not just the problematic ones—and crafting messages to induce them into productive deliberative relationships. The specifics depend on context, but might (for example) include a populist discourse that stresses plutocrats not cultural elites as the key enemy.

The mobilization of society-wide deliberative capacity is most visible in spectacular moments in the history of democracy. Such moments include the “autumn of the people” in East-Central Europe in 1989, in the “people power” that overthrew an autocrat in the Philippines in 1986, in “color revolutions” in Georgia (2003) and Ukraine (2004/2005), in Ukraine’s “Euromaidan” moment in 2013-2014, and in Chile’s estallido in 2019. Such mobilization can also be found in the deeper history of the United States—Ackerman identifies key episodes of inclusive public deliberation in the United States in connection with the founding, the post-civil war amendments to the constitution and the New Deal.

The fact that some of these moments were followed by subsequent autocratization shows that democracy is always something that must be fought for, rather than taken for granted. And in this fight, the deliberative capacity of society as a whole, not just the formal legacy institutions of the liberal democratic state, is crucial.

Editor’s note: This is an extra edition of the Perspectives on Democracy series for October 2025.

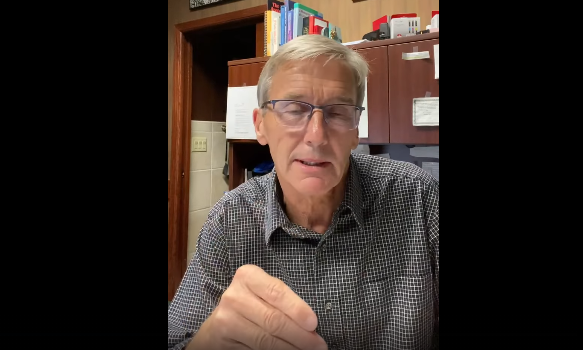

John Dryzek

John Dryzek is Distinguished Professor in the Centre for Deliberative Democracy at the University of Canberra, working in democratic theory and practice and environmental politics. His most recent book isDeliberative Democracy for Diabolical Times: Confronting Populism, Extremism, Denial, and Authoritarianism (Cambridge University Press 2024, with André Bächtiger).

.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·